Deseret Peak ranks as only the 199th highest peak in Utah, but it ranks fourth in prominence at 5,812 feet. The peak is located in the Stansbury Mountains, about one hour west of Salt Lake City and the trailhead can be accessed with a 2WD vehicle. This hidden gem sees relatively little traffic, especially compared to the many popular peaks along the Wasatch Front. The scenery is spectacular and the summit offers dramatic views of the Wasatch Front, Great Salt Lake and mountain ranges of the Basin and Range Province.

Trailhead at 7,424 ft (2,263 m) | Summit at 11,035 Ft (3,663 m) |

Total Elevation Gain of 3,900 ft (1,190 m) | Loop Trail of 8.3 miles (13.4 km) |

Hiking Time from 5-8 hours | Several Class 2 (YDS) Sections; Upper Part |

This is great hike to get a feel for hiking in the Basin and Range and get away from the Wasatch Front crowds. The hike is physically challenging, but relatively non-technical. There are some class two sections on the ridge lines near the summit. These parts could intimidate those with a fear of heights.

The trail classification system used in this blog is the YDS, Yosemite Decimal System

https://www.devilslakeclimbingguides.com/blog/understanding-climbing-ratings

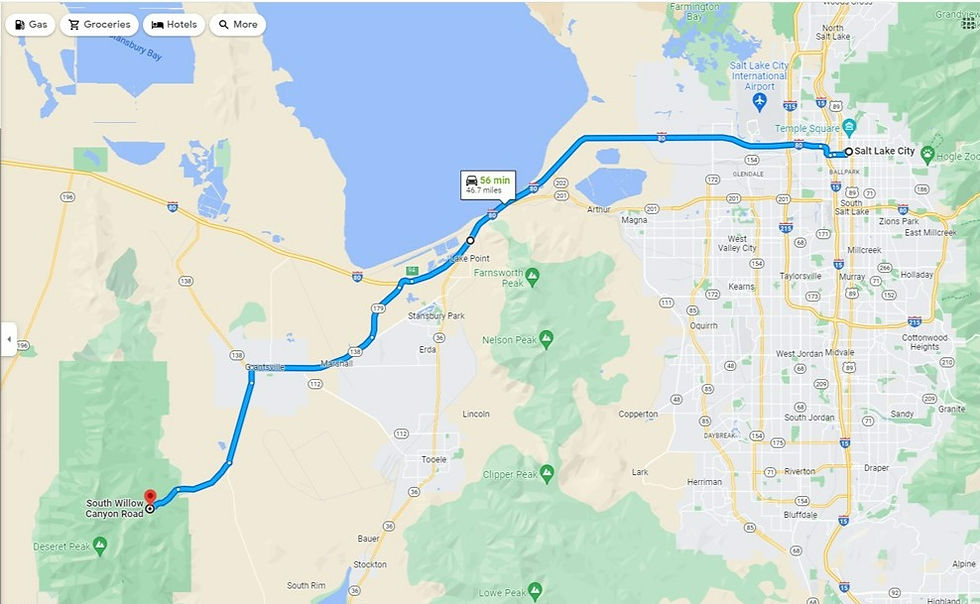

Directions

From Salt Lake City it is approximately 47 miles to the trailhead and takes about one hour.

Take I-80 west, about twenty-seven miles, to Exit 94, SR 179 (Midvalley Hwy) at Lake Point. Follow SR 179 for three miles to where it merges with Utah 138. Follow Utah 138 for an additional seven miles to West Street in Grantsville, make a left on West Street, heading south. In 0.8 miles West Street turns into the Mormon Trail and in an additional 4.3 miles you make a right onto S. Willow Canyon Rd. This good dirt road ends in 5 miles, at the Loop Campground, the trailhead is near the port-a potty. A 2WD vehicle should have no issues making it to the trailhead.

Trail Info

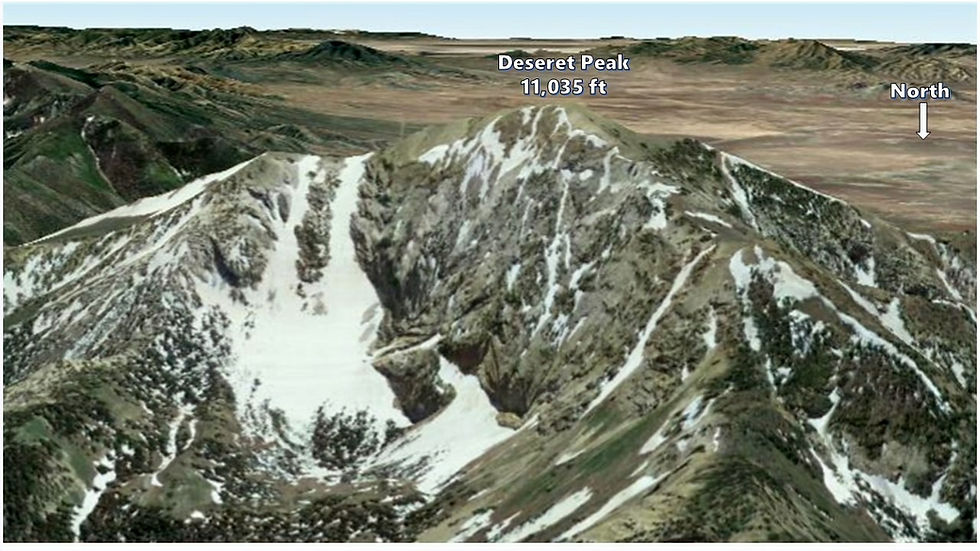

The Google Earth image below shows the area with some snow, likely taken in the late spring or early summer. We hiked on Sept. 30, 2017. Earlier that month there were a couple of early snow storms. We encountered over a foot of new snow in places, mostly between Points 4 & 5, near the peak and on the upper ridge lines. For us, route finding was a bit of a challenge on the way down between points 4 to 5. Overall, we just stayed on the ridge line when in doubt and always found the trail again.

These mountains are popular with hunters, so if you are going in the fall, I suggest wearing bright clothing and talking loudly with you hiking companions.

Loop Trail to Deseret Peak Going Clockwise

Trailhead is at the western end of the camping/parking area.

Marker 1 - 0.7 miles from the trailhead. At the fork, go left, this is Mill Creek, which you follow uphill for 1.8 miles.

Marker 2 - At 2.5 miles, the valley ends, you then begin to switchback up a steep slope to an E-W trending ridgeline.

Marker 3 - At 3.3 miles turn right at the ridgeline, heading southwest, then west to the summit, a large low relief knob.

Marker 4 - After hiking 3.9 miles you have reached the summit. At the summit, either go back the way you came or descend following a series of ridge lines downhill in a northerly direction for 1.6 miles. This is the most difficult part of the trail, as the trail is faint in places and there is some exposure. Most of the class two sections are from Marker 4 to Marker 5.

Marker 5 - at 5.5 miles leave the ridgeline and go down the slope in a NE direction.

Marker 6 - at the 6 mile point, you reach a fork in the trail, go right, the trail heads easterly, then south back towards the peak.

Marker 7 - at 7 miles, cross a small stream and the trail does almost a 180, heading north, then slowly it begins to trend to the east.

Marker 1 (again) - at 7.6 miles, you are back at the fork from earlier in the hike, go left, downhill towards the trailhead.

Trailhead - at 8.3 miles you are back at the start of your hike.

I recommend the loop route, either clockwise or counter clockwise, we went clockwise. The faster route is to take the fork to your left at Point 1 and return the same way. The longest is to take the fork to your right at Point 1 and return the same way.

Although, I suggest the loop, there are several class 2 sections with some exposure between Points 4 & 5, making this the most difficult section of the hike. Also, parts of the trail are faint along this section. Next time I would go counterclockwise, since it's usually easier to follow a faint trail going uphill rather than following it downhill.

The photo below was taken on our way down, between Points 6 and 7. Deseret Peak is the highest point on the ridge line to the right of the two couloirs; these can be skied into early summer.

The views from the summit are fabulous on a clear day. Looking north-north-east you will see the Great Salt Lake, along with Antelope Island. To the east, in the foreground, are the Oquirrh Mountains which partially obscure the Wasatch mountains near Salt Lake City. Some of the higher Wasatch peaks can be seen over the tops of the Oquirrhs.

Mt. Timpanogos lies off to the ESE and Mt. Nebo is about 60 miles to the south-east

To the west, numerous mountain ranges of the basin and range province can be seen. The valley on the west side of the range is Skull Valley and the next mountains to the west are the Cedar Mountains. Eighty miles to the south-west are the high peaks of the Deep Creek Mountains. This range has two peaks over 12,000 feet; Ibapah at 12,087 ft. and Haystack at 12,020 ft.

As you depart the peak, stay near the ridge line if you are not sure where the trail goes. The photo below, likely taken as we approached Marker 5. The trail is behind the trees in the left foreground. The peak in the upper-middle left is a few hundred of feet below the summit.

My friend Jane and her dog Stark as we descended toward the trailhead, dogs and horses are allowed on the trail. We were mostly alone, encountering a few hikers on the way to the peak, but none of them followed us to the summit. We did not pass or see a anyone on the way back to the trailhead.

Camping

The Loop Campground, at the trailhead consists of thirteen campsites with dirt pads. These are modest campsites without water or electricity, but each has a picnic table and flat area for camping. The campground is a nice secluded area surrounded by aspens, box elder trees and Douglas fir. We did not camp the night before our hike, as we were unaware the campsite existed.

Even though the trailhead is close to Salt Lake and Provo, I would consider driving up the afternoon before hiking. This will provide you with a pleasant evening in the outdoors and no need to drive the morning of your hike.

History

In 1984 Congress established the Deseret Peak Wilderness, an area of 25,000 acre on National Forest lands in the center of the Stansbury Mountains. The range was named after Capt. Howard Stansbury, who led a U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers expedition in 1849-50 to survey the Great Salt Lake and its vicinity.

Based on archaeological evidence the earliest artifacts place Native Americans in this area about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. These paleolithic people lived near Great Basin wetlands. As these wetlands disappeared over the centuries, the paleolithic people were replaced by the Desert Archaic people. Evidence of Archaic people was found in caves near the Great Salt Lake, their population started to decrease about 3,500 years ago as lake levels rose in the area.

The next migration were Native Americans of the Fremont Culture, they lived in the area from about 600 AD until 1000 AD. As this culture faded, it was replaced by the Goshute Indians who migrated to the area and assimilated the Fremont Indians.

The Goshutes were hunter-gathers who lived a subsistence life style. Living mostly off of seasonal seeds, pine nuts, roots, insects and small reptiles. Hunting small game, antelopes and deer provided some supplementary food to their merger diet.

In 1847 the Mormons arrived and the Goshute lifestyle began to unravel as settlers encroached on their land. The Goshutes were moved to two reservations in the eastern part of the Great Basin early in the twentieth century. One of these is in Skull Valley on the west side of the Stansbury Mountains, the other is on the west side of the Deep Creek Mountains. Today the remaining small population still live on these reservations and in the communities near-by.

Flora and Fauna

The high mountain ranges of the Great Basin are botanically unique due to their isolated montane , subalpine and alpine floras. Surrounded by desert, these island-like ranges have characteristics in common with oceanic islands (Harper et al.1978). The Stansbury Mountains, are some what unique, their flora being transitional between the Great Basin ranges and the Wasatch Mountains. (Taye, Alan C. 1983)

Several distinct vegetation zones exist in the Stansbury Mountains. In order of increasing elevation, the semiarid valley floors consist of shadscale, sagebrush and grass, the foothills began around 5,000 feet, with the flanks of the mountain speckled with juniper trees. At about 7,500 feet you enter the montane live zone where the juniper trees are replaced by Douglas fir and white fir. You enter the subalpine life zone at From 9000 ft. where you encounter Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir. This range also contains some bristlecone pine intermixed with limber pine, usually found above 10,000 feet. The alpine zone begins at 10,500 ft. on the upper ridges and peaks, where only small scrubs and plants are found.

The range contains approximately 180 species of animals according to the BLM;114 are bird species, 51 are mammals, and 15 are reptiles. These including mule deer, badgers, bobcats and mountain lions, along with numerous smaller mammals. Seventeen species of raptors are found in the area, including the occasional sighting of both bald and golden eagles in the northern part of the range.

Geology

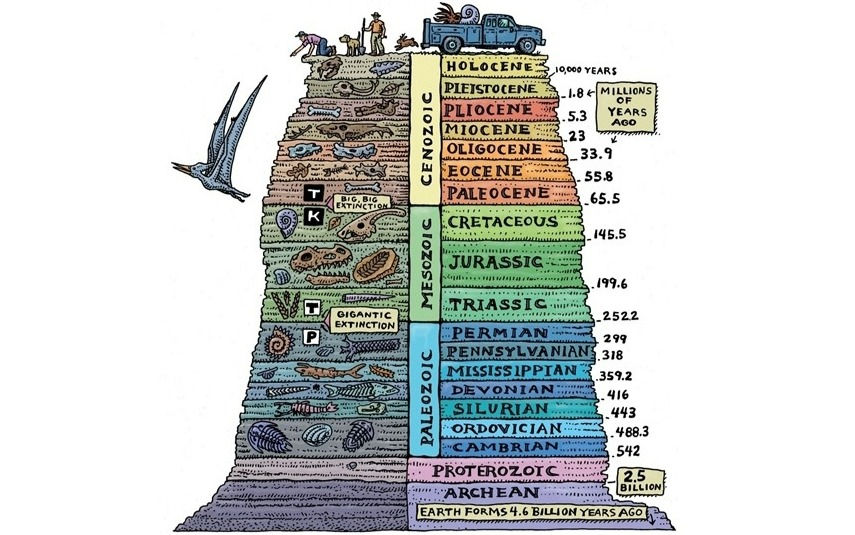

The Stansbury Mountains are a 26 miles long N-S trending anticline with a width of up to ten miles. Structurally the range is a large eastern tilted block. The peaks and ridges are composed of Paleozoic sediments, with the oldest sediments making up the central part of the range. Mountain valleys are filled with glacial till and stream alluvium. The range is structurally complex due to Paleozoic uplift, followed by Mesozoic compression, then during the Cenozoic, the extensional tectonics that formed the Basin and Range Province.

Evidence of Lake Bonneville in the form of terraces and wave-cut cliffs can be found around the base of the range.

As you drive to the trailhead the youngest hills, near the valley floor, are composed of Eocene volcanics, you then pass a section of hills composed of Pennsylvanian to Mississippian age limestones, sandstones and shales. These sit unconformably on the Cambrian sediments, predominately quartzites, that make up the hills and ridges that surround Deseret Peak. . Once you start hiking to Deseret Peak, all the hills you pass are composed of these Cambrian age rocks.

The U-shaped valleys surrounding Deseret Peak were carved by multiple episodes of glaciation, with the last glaciers disappearing about 14,000 years ago. The valley fill is glacial till left behind as the last glaciers retreated. Numerous cirques can be seen from the summit and there are small lakes in two of the cirque basins.

Comments