- Ronald (Steve) Boulter

- Nov 6, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 8, 2023

Overview

Provo Peak is Utah's 24th highest peak at 11,068 ft, and the 28th most prominent at 3,428 ft. The peak is located in the central Wasatch Front; behind Provo City and is a dog friendly trail.

This is a short, steep, trial. It is not for first time peak baggers or small children. The trail is easy to follow as it winds it's way up the steep ridge to the summit. Most folks would find trekking poles useful on this hike. I found them invaluable while hiking down.

Trailhead at 8,343 ft (2,543 m) | Summit at 11,068 ft (3.374 m) |

Total elevation gain of 2,750 ft (838 m) | Roundtrip of 2.9 mi (4.7km) |

Time from 3 to 6 hours | Mix of class1 trail and class 2 (YDS) |

The trail classification system used in this blog is the YDS, Yosemite Decimal System

We summited around noon on Saturday, September, 10, 2022. Our round trip hike took almost five hours, including a leisurely lunch on the summit. This was a fairly slow pace, made obvious, since we were passed by several other hikers on our way up.

From the summit you can see Cascade Peak five miles to the NNW and Mount Timpanogos sits six miles behind Cascade Peak. Thirty miles to the SSW is Mount Nebo, the highest peak on the Wasatch Front. Closer are several glacial cirques adjacent to Provo Peak.

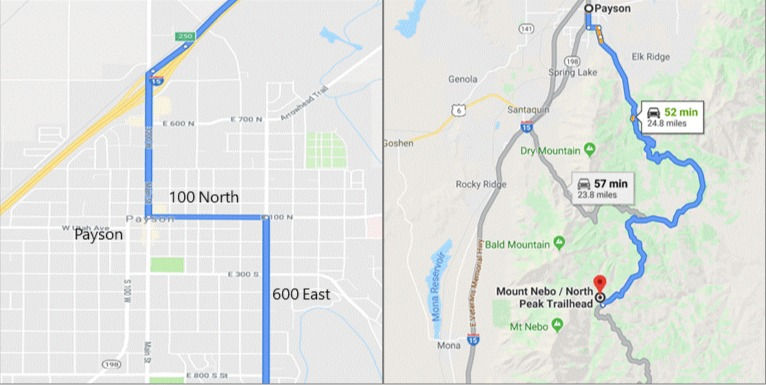

Directions

There are two trails to the peak, these directions take you to the trailhead of the shorter hike.

From the mouth of Provo Canyon drive up the canyon heading easterly for 1.8 miles. Turn right at Squaw Peak Rd. and drive 13.4 miles to the trailhead. The drive takes about an hour from the Squaw Peak turnoff.

The Squaw Peak Rd. starts out as a paved road, but soon turns into a well maintained dirt road. After 11.4 miles you will reach the turnoff for the Rock Canyon campground turnoff. At this point there is a road sign warns that a high clearance AWD vehicle is required to proceed up the Squaw Peak Rd. We found the road to be in good shape over this last 3.8 miles to the trailhead. This section is rough in places and requires some slow driving, but we had no clearance issues in our Outback.

Trail Info

There are two trailheads to the peak, the longer route is the Slide Canyon Trail at 11.4 miles with a cumulative elevation gain of 6,700 feet.

The shorter route, our choice, is just under 3 miles roundtrip and is accessed by the Squaw Peak Rd. This is a tough but short hike; you gain 2,700 feet in only 1.46 miles.

This hike is not technical and the trail is easy to follow up the steep ridgeline to the summit. You should be comfortable hiking on loose scree and there is no water along the hike and no shade after the first 0.9 miles.

The trail begins by crossing the road from the parking area and following a very rough dirt road that heads in a northerly direction. You will be hiking mostly in aspen trees along this road and the first section of the trail.

0.0 mi ( 8,343 ft) to 0.4 mi (8,800 ft) -- Follow the 4X4 dirt road across from the trailhead parking area, at 0.4 miles turn right at the rock cairn. You are now on the trail to the summit.

0.4 mi (8,800 ft) to 0.9 mi (9,780 ft) -- This section starts in aspens and ends as you exit the last large bushes. The gradient, over this section, is moderate.

0.9 mi (9,780 ft) to 01.2 mi (10,490 ft) -- This is the steepest section of the hike, the trail is faint in places, so just stay on or near the ridge line.

1.2 mi (10,490 ft) to 01.46 mi (11,068 ft) -- This last section to the summit is slightly less steep than the previous section. Once again stay near the ridge, but overall the trail is fairly obvious.

In the photo below, we had just turned off the rough dirt road and onto the trail to the summit.

Below, we are above the aspens and large bushes and have started up the steepest section of the hike.

Below, one of the hikers who passed us on the steep section.

Our group at the summit, it took us about 2.5 hours to summit. After a nice lunch break, the return hike took about two hours

The day we hiked smoke from an Idaho fire was moderately thick in Utah Valley. Looking NNW are Cascade Peak and Mount Timpanogos, respectively six and eleven miles away. Due to the smoke, Mount Timpanogos was barely visible in the background.

Below, my son and daughter-in-law, picking their way down the trail a few hundred feet below the summit. In the far background sits Provo, again partially obscured due to the smoke.

History

10000 BC to 6500 BC -- Paleo-Indians who subsisted on hunting and plant gathering.

650 BC to 400 AD -- The Archaic Cultures also lived as hunter-gathers.

400 AD to 1300 AD -- The Fremont people were the first to introduce and live off of agriculture.

1300 AD to 1800 AD -- The Timpanogots (Utah Valley Utes) reverted back to a hunter-gather lifestyle.

1847 to present -- The Mormons arrived and stayed, introducing agriculture and industrialization.

The first documented human inhabitants near the Wasatch Front were the Paleo-Indians, who followed migrating big game into Utah. The nearest Paleo-Indian archeological sites are found along the Old River Bed delta, located in Dugway Proving Grounds, Utah. Then there is a long gap from 6,500 BC to 650 BC with no documented human habitation in this area.

The second documented group were Archaic people who dominated the area from 650 BC to 400 AD. They hunted small and midsized mammals and collected plant foods in Utah and Juab Valleys. Two Archaic camps have been excavated in the area: one at American Fork Cave and the other at Wolf Springs near Heber, Utah.

The first farming started around 400 A.D. when the Fremont people migrated into central Utah, likely from the south. They lived in scattered farmsteads and small villages in the valleys and benches of the Wasatch Front. They farmed corn, beans and squash and supplemented this with collecting wild plants and hunting game. Around 1300 A.D. the Fremont people abandoned their villages when the climate became colder making farming corn unreliable.

By A.D. 1300, the Numic people had settled across the Great Basin, likely arriving from southern California and/or northern Mexico. They replaced the Fremont people in northern and central Utah. These Numic people survived on hunting and gathering. Around 1400 A.D. the Utes and Goshutes, two distinct groups of Numic people, settled the lands in and around the Utah Valley.

The Utes that settled in Utah Valley, were known as the Timpanogots. Believed to have been named after Lake Timpanogos (Utah Lake). When the first Europeans arrived, Ute villages were located on the eastern side of Utah Valley along the rivers flowing into Utah Lake. Then in 1847, the Mormons arrived bring industrialization and advanced farming techniques.

Overgrazing in the early 1900s resulted in significant erosion along the higher elevations of the Wasatch Range. To combat this erosion and provided depression era jobs a vast system of erosion control terraces were built by the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) during the 1930s. Numerous erosion control terraces can be seen on the hillsides of Provo Peak and the nearby mountains.

Primary website used for the history section

Flora and Fauna

This short hike exposes you to three climate ecozones, you start in the upper montane forest, transition to the subalpine zone for the second half of the hike, and cross into the alpine zone near the summit.

You start the hike in the upper montane forest. This zone is dominated by conifer forests and aspen groves. This trail wanders mostly through quaking aspens, with only the occasional conifer tree along the way. Although we saw no large mammals; elk, mule deer, black bears and cougars roam these forests.

The transition from upper montane forest to the subalpine zone begins when you exit the aspen trees and enter a patch of large bushes about 0.5 miles up the trail. These bushes stop at about 0.9 miles and 9,800 feet as you approach the long exposed ridgeline to the summit. Vegetation in this subalpine zone is determined by slope direction and wind exposure.

Once on the exposed ridge line you will find the slopes on the north side dominated by conifer trees and the southern facing slopes are dominated by grasses and small bushes. The actual ridge line is dominated by scree, grasses, flowers and small bushes. Your main animal company here will be small mammals and birds.

The transition from subalpine to alpine is near the summit, give or take a hundred feet. The alpine zone is free of trees and dominated by small plants, bushes and some flowers. Life is difficult here due to high winds and extreme cold much of the year.

Geology

At the Provo Peak trailhead you are standing on Mississippian age Manning Canyon Shale. Once you start up the trail you soon transition to younger Pennsylvanian age limestones, dolomites, shales and sandstones of the Oquirrh Formation. The rest of the hike is on Oquirrh Formation rocks. You just transition from older to younger Oquirrh Formation rocks as you climb higher.

Provo Peak is located in the Wasatch Range, a string of impressive peaks that run north-south bisecting the state of Utah. This range is also the western boundary of the Rocky Mountains in Utah.

The range is relatively young. Normal faulting and uplift of the range began about 12 to 17 million years ago, during the Miocene, and is still on going today. The numerus active faults associated with the Wasatch Range provides evidence of ongoing mountain building today.

Like most of the taller peaks in the Wasatch Range, Provo Peak was shaped by numerus episodes of glaciation. Glacial cirques make up the sides of many of the nearby peaks and large U shaped valleys are common at the higher elevations. The most recent glaciation ended about 20,000 years ago, when glaciers from the last ice age began to retreat as the climate warmed.